Tale of the Bear Creek Meteorite, Jefferson County, Colorado

2022-03-09 | CGS Admin

By Matthew Morgan, Deputy Director, Colorado Geological Survey and Gary Curtiss, Lakewood geologist and meteorite collector

The prior discovery by George R. Morrison of the Bear Creek iron meteorite was confirmed on April 18, 1866 when Morrison and James L. Wilson returned to a location approximately 48 km (30 mi) west of Denver on the eastern slope of the Front Range in Jefferson County, deep in a ravine at an elevation of about 2400 m (7875 ft). The “ravine” is presumably Bear Creek which runs through the town of Morrison—this would explain the official name of the meteorite. There are conflicting reports as to the actual weight of the original specimen—the finders indicate that it weighed about 227 kgs (500 lbs), but others who were given pieces of the meteorite estimated its weight at 360 kg (800 lbs). The official weight given in the Meteoritical Bulletin is 227 kgs (500 lbs). Morrison and Wilson announced their unique find in a May 14, 1866 article published in the Rocky Mountain News:

On the 18th ult.*, in company with Mr. G.R. Morrison, we found it in the bottom of a gulch, where a freshet had washed away the loose stones and earth and exposed it. Mr. Morrison had seen it before, and taking it of blossom rock had spent some time in searching for the lode, and is therefore entitled to the credit of its discovery. It was irregular in form, about 22 inches long, 9 to 10 thick and 14 wide. Four of its sides are flat and two rounded. This form indicates it to be a fragment of a much larger mass. It is magnetic-weight about 500 pounds. The force with which it struck the rocks at the time of its fall has so shattered one end of it as enabled us to break off a piece that weighed eleven pounds. Its composition appears to be the native metals of nickel, cobalt, iron and a trace of copper, unequally distributed in the mass. In one part nickel and cobalt are largely in excess of the other metals while in other parts iron forms the chief ingredient. These metals are aggregated and highly crystallized. A coating of the oxide of iron half an inch thick has taken the place of the shining black crust observed on aerolites when they first reach the earth. The less oxidizable metals of nickel and cobalt still remain in their metallic state in this coating of iron rust.

A curious interest has always been manifest in these strange wonders, which in former times led to many fanciful and absurd conjectures, as to their origin, and the laws governing them. Fireballs, shooting stars and meteoric stones all come under the general appellation of aerolites.

* [Ed: “ult.” isn’t a typo, it’s a Latin abbreviation for ultimo mense, or last month.]

Their description of the piece indicates that the meteorite may have collided with a rock ledge and was fractured. Due to the fractures, the finders were able to remove several pieces of the meteorite for examination. They also noted that the meteorite was covered by a half inch-thick layer of iron oxide—a weathering product indicating that the meteorite probably fell at least several hundred or perhaps thousands of years before it was found. J. Alden Smith (of Trail Run, Colorado Territory) wrote briefly of the Bear Creek meteorite in The Daily Mining Journal of October 26, 1866, indicating that the mass was found on a bed of solid gneiss and was shattered on one end which enabled the removal of an 11 lb (5 kg) piece for his analysis. Later in life, J. Alden Smith became the first Territorial Geologist for Colorado from 1874-1883 and the first State Geologist from 1885-1887 when Colorado gained statehood.

Morrison and Wilson, although accomplished prospectors, lacked the knowledge to properly identify meteorites. They relied upon Smith, who was a local mining expert and Mining Editor of the Central City Register Call, to provide his opinion on the chemical composition and origin of the specimen. After assaying the Bear Creek iron, Smith believed it was a meteorite and sent two samples elsewhere for additional opinions. The first sample went to the San Francisco Mining and Scientific Press. Their reply was that the sample was a sulphide of iron ore and not ‘meteoric’ in origin. The second sample was sent to Benjamin Silliman, Jr. and James D. Dana (the famous geologist and mineralogist) at the American Journal of Science and Arts located in New Haven, Connecticut. They were the leading meteorite experts in the country. The sample was recognized as a meteorite and their assistant, C. U. Shepard, published the first scholarly report of the Bear Creek meteorite. At this time in 1866, Shepard had amassed the largest meteorite collection in the world and became fascinated with the Bear Creek iron meteorite. Thus, the November 1866 issue of the American Journal of Science and Arts announced that ‘Prof. Shepard, through the agency of a friend in Denver City has secured the original mass for his cabinet.’

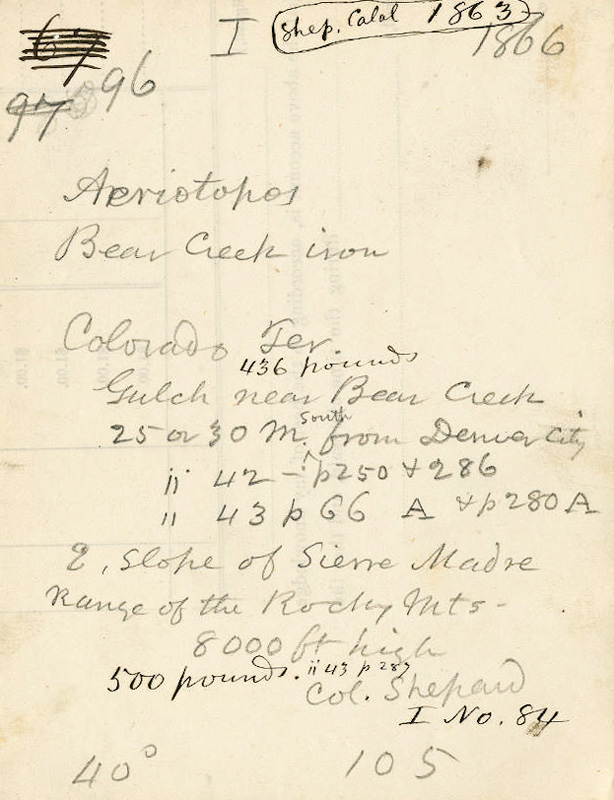

The 227 kg mass (less 5 kgs provided to Alden) was dissected for research and distributed to institutions with the main mass ending up in the Amherst College (Massachusetts) Collection curated by Shepard. At Amherst, the meteorite was catalogued under the Latin name Aeriotopos, ‘topos‘ meaning ‘place’ and ‘aerio‘ meaning ‘high in elevation.’ According to Shepard, in 1866, Smith sent him a piece of the meteorite 1.5 inches long by 3/5 inches wide and 1/8 inch thick. He indicated that Wilson and Morrison showed Smith the location, but a detailed description of the location was never published. In 1871, Shepard published a catalog of his meteorite collection which was at the time housed at the Wood’s Building of Amherst. A note in Nature Magazine stated that the “Aeriotopos” was the heaviest iron in the collection, weighing 198 kgs (438 pounds); however, Shepard’s original collection label (Figure 1) indicates a weight of “436 pounds” (197.7 kgs).

Following the trail of the Bear Creek meteorite

The 1909 Catalogue of the Meteorites of North America lists 436 lbs (197.7 kgs) of the Bear Creek meteorite in the Amherst Collection. This is corroborated by the Shepard Collection label.

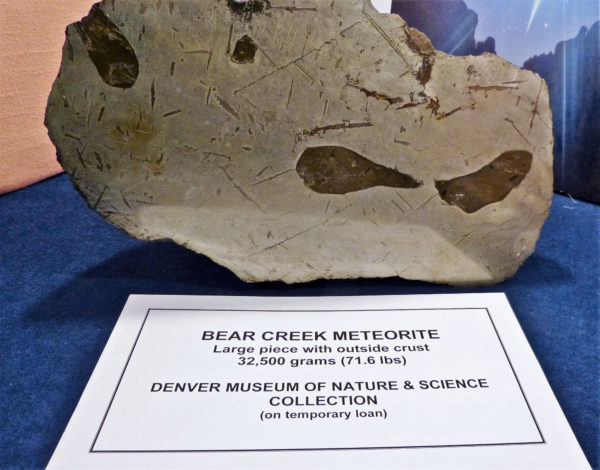

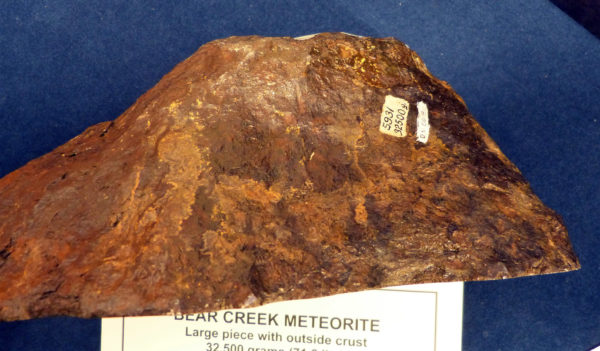

As recorded in the Bailey Archives of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (DMNS), on December 9, 1935, a proposal by the Colorado Museum of Natural History (now the DMNS) listed ten meteorites to be ‘retained’ by the Museum from the Amherst Collection. Topping the list was an ‘end piece’ of Bear Creek weighing 32.5 kg (72 lbs) (Figure 2)—and note that adding the 32.5 kgs in Denver to the 197.7 kgs at Amherst, the Bear Creek meteorite weigh 203.2 kgs (507 lbs).

Between 1930 and 1945 famed meteorite hunter Harvey H. Nininger had received a small salary from the Colorado Museum (DMNS) to establish his headquarters there, place his collection on display, and to act as curator. So, it seems safe to assume that Nininger facilitated the meteorite exchange with Amherst that included the acquisition of the Bear Creek meteorite end piece. There is no direct evidence to show if he actually owned the end piece or was just instrumental in getting the piece to the Colorado museum. The catalog number on the piece is #5931 which does not cross-reference to any of Nininger’s personal collection pieces (Figure 3). Also, Nininger owned a complete 8,720 g slice that is listed in the Nininger Collection of Meteorites (1950) with catalog number 352.1 and a photo that is of similar appearance to the DMNS specimen cut face. It is unknown as to how or where Nininger obtained this slice.

The 1953 and 1966 Catalogue of Meteorites lists the Bear Creek main mass still at Amherst College.

The 1970 Catalog of Meteorites at Arizona State University (ASU) shows one slice weighing 4.093 kgs (9 lbs).

According to the Handbook of Iron Meteorites as of 1975, the largest pieces of the Bear Creek meteorite were in the following institutional collections (note the Denver piece has the incorrect weight): Amherst (160 kg), Denver (35 kg end piece), London (4.4 kg), Tempe (4.2 kg), Washington (275 g), Gottingen (235 g), Yale (156 g), Chicago (129 g), New York (116 g), Chicago (17 g).

In 1985, ASU updated their collection catalog with new acquisitions. It listed a total of 160 kgs (353 lbs) of Bear Creek in its collection consisting of the 124 kg main mass (273 lbs) and five slices weighing from 4.8 kgs (10.5 lbs) to 8.3 kgs (18.3 lbs). The catalog also notes that ASU acquired the C.U. Shepard Collection from Amherst College in 1978 including the Bear Creek main mass of 124 kgs (273 pounds).

The 2019 ASU Catalog shows that ASU still had 90.495 kgs (199 lbs) of the Bear Creek meteorite, the remaining main mass.

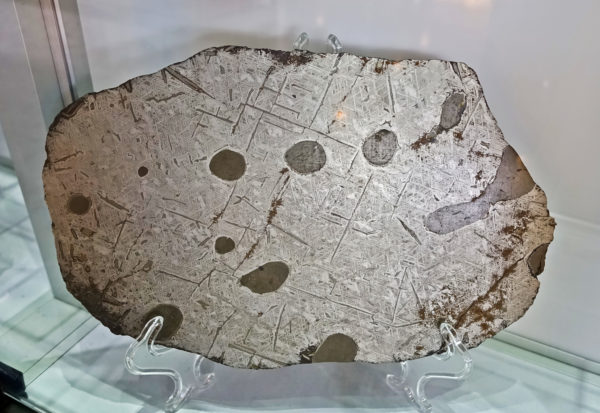

Classified as a IIIAB iron, the Bear Creek meteorite contains 9.95% Ni, 0.54% Co, 0.7% P, 2% S, 18.8 ppm Ga, 32.8 ppm Ge, 0.06 ppm lr. Cut and etched surfaces reveal a well-developed Widmanstätten pattern (Thomson structures) with kamacite (α-(Fe,Ni); Fe0+0.9Ni0.1) crystal planes ~0.60 mm in width. Numerous troilite (FeS) nodules are dispersed throughout the mass and are visible as dull-gray circular inclusions.

Ed: And just to note that if you are in or near Golden, Colorado, the Mines Museum of Earth Science has a fine display of meteorites among 15,000 sq ft of rocks, minerals, fossils and other fascinating Earth Science-related objects!